Shishak (Shoshenq I) of Egypt was one of the few foreign kings named in the Bible and was known for his raid in Jerusalem during the time of Rehoboam. He can be found on the Bible Timeline around 979 BC. 2 Chronicles 12 offers a detailed account of Shishak’s raid on Jerusalem, which happened in the fifth year of Rehoboam’s reign. Shishak took with him thousands of chariots, horses, and soldiers to strike the fortified towns of Judah. These towns fell under the onslaught of Shishak’s troops, and they continued to Jerusalem for another wave of attacks. Shishak then invaded Jerusalem and looted the treasures of the Lord’s Temple. He also stole the treasures of Solomon’s royal palace including the gold shields, which were replaced by Rehoboam with bronze shields.

Quickly See 6000 Years of Bible and World History Together

Unique Circular Format – see more in less space.

Learn facts that you can’t learn just from reading the Bible

Attractive design ideal for your home, office, church …

Libyan Origin and Rise to Power

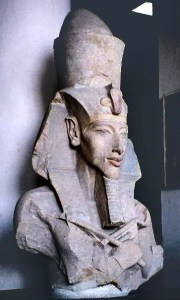

The Libyans who lived on the coast of Marmarica and Cyrenaica first appeared during the rule of the 18th Dynasty Pharaoh Akhenaten. They were included as military escorts of the king. High ranking Libyans also accompanied Egyptian nobility to temple ceremonies. Evidence of this can be seen on various stone reliefs in the Tomb of Ahmose and Meryra at Amarna.

The Meshwesh and Libu tribes raided Egyptians territories and clashes with the Egyptian troops were common at the time of the 19th and 20th Dynasties. Libyan immigrants also settled in the nome of Bubastis in the Nile Delta during periods of famine, but some of them were children of early Libyan garrison troops who grew up in Egypt. As centuries passed, the population of the immigrants increased and they successfully integrated into the Egyptian society. Their chieftains also gained enough wealth and power to marry into Egyptian noble families.

Shoshenq I was one of the first Meshwesh chieftains who rose to power, and he became the second Pharaoh of Libyan origin after his uncle Osorkon, the Elder. Marriage with some of the members of the royal family also played an important role in easing Shoshenq’s rise to power. He arranged the marriage between his son Osorkon I and Maatkare, the daughter of Psusennes II who was the last Egyptian pharaoh of the 21st Dynasty.

Rule of Egypt

The 21st Dynasty was marked by a division of power between the pharaohs ruling from Tanis in Lower Egypt and the High Priests of Amun based in Thebes in Upper Egypt. Shoshenq unified political authority under his rule and ensured that the high priests would not hold as much power as the pharaoh held. Priests were consulted for oracles, but they did not influence political decisions and foreign policies.

He appointed his own son, Prince Iuput, as a High Priest of Thebes to strengthen his own rule and reduce the power of other priests. Iuput was also the commander-in-chief of the army and governor of Upper Egypt. The loyalty of family members and supporters was rewarded with their appointment to administrative posts, as well as marriages to royal daughters.

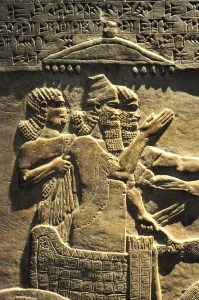

Shoshenq had planned on building a great court in the temple of Amun at Karnak, but this remained unfinished at the time of his death. Shoshenq’s military victories were inscribed at the Bubastite Portal, which is the entrance to the Precinct of Amun-Re temple complex.

Invasion of Palestine and Death

Egypt’s influence over Palestine decreased during the division of political power of the 21st Dynasty. Shoshenq reestablished Egypt’s power over Palestine by launching a series of raids into a number of towns, including Shunem, Gibeon, Megiddo, Beth Horon, and Ajalon among others.

Shoshenq reestablished trade with Phoenicia during the time of King Abibaal of Byblos. A statue of Shoshenq I that had an inscription of Abibaal, was found in a temple in Byblos. It symbolized the goodwill between two kingdoms during their reign.

Shoshenq died shortly after his invasion of Palestine, and he was succeeded by his son Osorkon I as pharaoh.

http://penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/PDFs/29-3/Egyptians.pdf

Shaw, Ian, and John Taylor. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2000

Ash, Paul S. David, Solomon and Egypt: A Reassessment. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 1999. Accessed March 18, 2016

CC BY-SA 1.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58987